Fruits of peace: Struggling with violence and investment in Mindanao

October 19, 2015 at 10:30

Insurgency in the Philippines

Fruits of peace

Struggling with violence and investment in Mindanao

| DAVAO | From the print edition

IF YOU want a reason to be optimistic about the future of Mindanao in the southern Philippines, a region long racked by poverty and insurgency, look at Sasa port in the city of Davao. On a weekday morning it is bustling. Cranes stack the hold of a massive green ship with containers holding bananas, pineapples and coconuts—all bound for China’s hungry consumers. The Philippines is the world’s third-leading exporter of bananas. Three-quarters of the country’s production of the fruit comes from Mindanao, long known as the Philippines’ food basket. Between 2010 and 2014, the value of the country’s banana exports grew by 256%—faster than anywhere else in the world. Plantations in Mindanao played a big part.

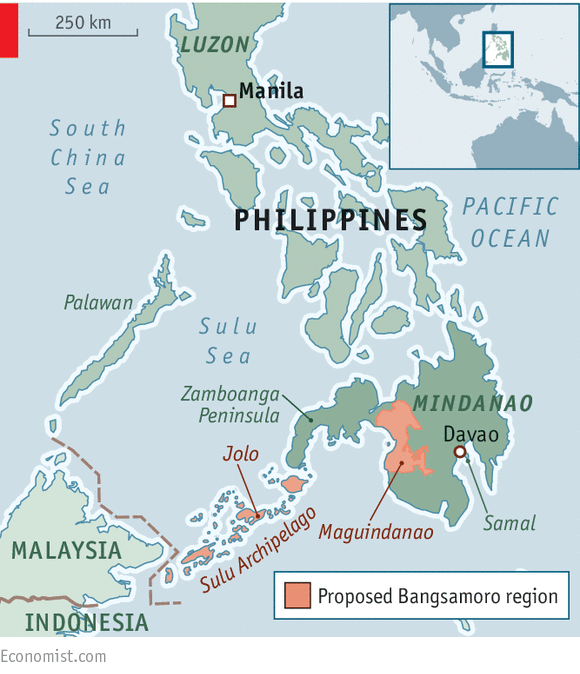

But if you want a reason to be pessimistic, look across the harbour to Samal, a small island studded with beach resorts and marinas. On September 21st kidnappers snatched four people—two Canadians, a Norwegian and a Filipina—and reportedly took them to Sulu, an archipelago in the Autonomous Region in Muslim Mindanao (ARMM), a patchwork of territory which Abu Sayyaf, an Islamist separatist group, has long used as a base. Philippine officials insist the kidnapping was an isolated case, but on October 7th an Italian businessman was abducted in Mindanao’s Zamboanga peninsula. A day earlier troops had foiled a plot by Abu Sayyaf to bomb Jolo, in Sulu; two days earlier bombs had toppled two power-transmission towers in central Mindanao.

Local officials remain sanguine, and investors do not appear to be running for the hills—yet. But efforts to achieve peace between the central government and the rebels of the Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF), the region’s largest separatist group, appear to have stalled. And though both sides appear to remain eager to reach a peace accord, delay raises the risk of more violence.

It was not always so gloomy. On March 27th last year the central government and the MILF signed an agreement on setting up a new autonomous region called Bangsamoro in majority-Muslim western Mindanao, to replace ARMM. In exchange the MILF would abolish its armed wing—thus, it was hoped, ending decades of armed struggle and capping a peace process that began 18 years earlier. President Benigno Aquino submitted the Bangsamoro Basic Law (BBL), which enacts the agreement, to Congress in September 2014.

Even before that, the MILF had stopped fighting. International lenders such as the World Bank had begun funding roads and development. Investment and central-government funds poured into Mindanao, which offers numerous advantages over the rest of the Philippines: abundant available land, comparatively low electricity rates, a location just outside the normal reach of typhoons and proximity to the large markets of Malaysia and Indonesia. Between 2010 and 2014 investment into Mindanao increased more than sixfold; between 2011 and the current fiscal year Mindanao’s allocation in the national budget more than doubled. Mr Aquino has allocated more in his single six-year term for desperately needed upgrades of infrastructure in Mindanao, such as roads and irrigation, than his predecessors did in the previous 12 years. In the Bangsamoro region, investment this year is likely to be more than five times the amount in 2013. Many people in Bangsamoro have traded guns for ploughshares.

In January, however, 44 policemen died in a botched raid on a rebel group in Maguindanao. Since then, the BBL has failed to make progress in the Philippine Senate, where it will probably continue to languish for the eight months left in Mr Aquino’s term. Supporting it will win few votes and could cost plenty.

Whether the BBL becomes law after that depends on whether Mr Aquino’s successor decides to refile it. Presidential hopefuls have until October 16th to submit their candidacy papers. A front-runner is Grace Poe, a senator, who opposes the BBL in its current form. This does not end hope for a durable settlement; the next president may remain open to negotiation. But the MILF risks splintering as it loses credibility with younger fighters, some of whom seem to be losing patience. And the virtuous cycle of peace spurring investment and development, which leads to a deeper peace, risks turning vicious.

Source: www.economist.com