Background (Mining)

Sector Background and Potential

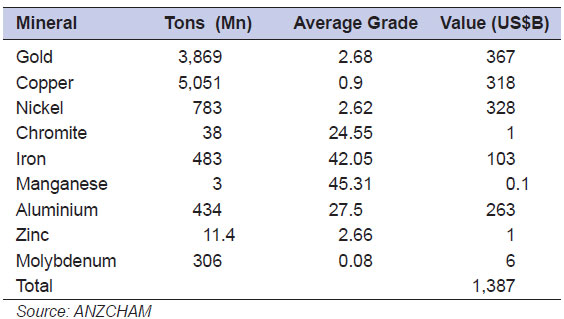

With an estimated US$ 1.4 trillion in mineral reserves, especially gold, copper, nickel, aluminum, and chromite, the mining potential of Philippines is one of largest in the world (see Table 51). According to the Mines and Geosciences Bureau (MGB), the archipelago is second in the world in gold and third in copper resources. The country is ranked top five in the world for overall mineral reserves, covering

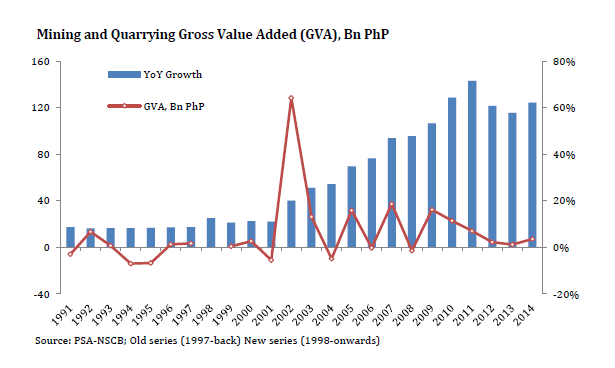

The Philippine mining industry is fortunate to have, aside from the country’s substantial mineral resources, a regulatory framework favorable and attractive to investment. After stagnating for almost a quarter century, the mining sector of the economy is making a comeback following a Supreme Court decision in 2005 affirming the Philippine Mining Act of 1995 (RA 7942) (see Figure 125).151

The Mining Act was intended to resuscitate the industry and replace a martial law presidential decree. It opened the doors to potential developers of mining projects. By providing significant social and environmental safety nets, the law is considered to be a model legal framework for sustainable development and among the best in the world. Mining must respect the community and environment, which proper implementation of the Philippine Mining Act will achieve. In comparison to other mining laws of other countries like the UK, US, Australia, and Canada where mining plays a strong role in the growth of their first world economies, the Mining Act is deemed as being at par, if not better, in including social and environmental obligations of mining companies.

Legal challenges delayed implementation for a decade until the Supreme Court in 2005 ruled with finality that the law is constitutional. Under the law, foreign investors can enter into Financial and/or Technical Assistance Agreements (FTAA) and be granted permits for exploration and mineral processing. Given the very significant capital requirements and long lead-times to develop large mines, this ruling opened the way for the industry to grow. In recent years, most of world’s largest mining companies have expressed serious interest to invest in the Philippines, with target investments ranging from hundreds of millions to several billion dollars.

Metallic minerals development is a major government priority with great potential for job creation and revenuegeneration. Mining can support poor rural areas through creating high quality jobs and through various local taxpayments and community and social development projects. The national government receives substantial royaltyand tax payments.

In 2009 the mining and quarrying employment, totalling 167,000 workers, was about 0.5% of total employment in the country. Government revenue from various fees, royalties, and taxes paid by mining firms has increased from PhP 1.4 billion in 2002 to PhP 10.4 billion in 2007 and PhP 7.6 billion in 2008, many times the amount of revenue before the new policy was put into effect.152

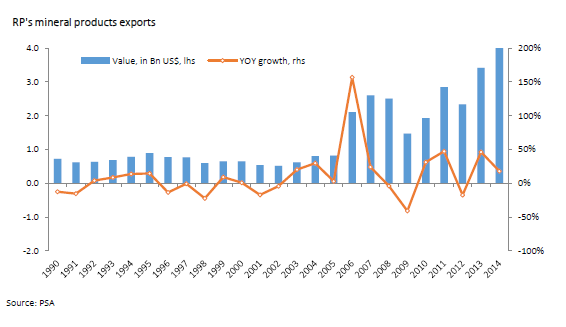

In 2009, metallic mining activities accounted for 1.3% of GDP or PhP 111.5 billion, and the value of mineral exports reached US$ 1.5 billion, but only 3.8% of the total value of goods were exported (see Figure 126).153

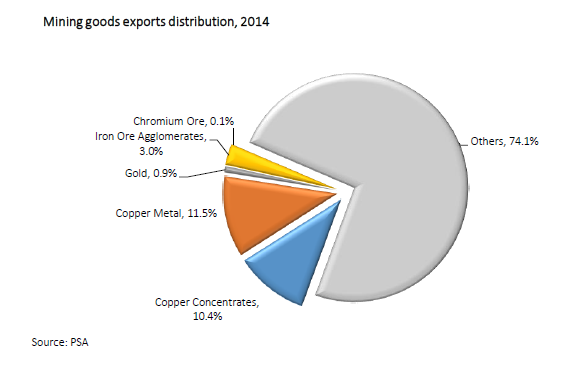

Figure 127 shows the distribution by metal type of Philippine mining goods exports in 2009. More local value could be added and more jobs created if mineral ores are processed more in the Philippines. While labor costs are competitive, processing is power-intensive, and the high cost of electricity, except in Mindanao, may discourage such investments. However, copper metal which already accounts for nearly half the value of total exports, is a good example of processing in the country.

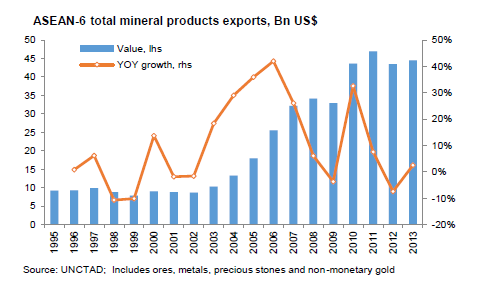

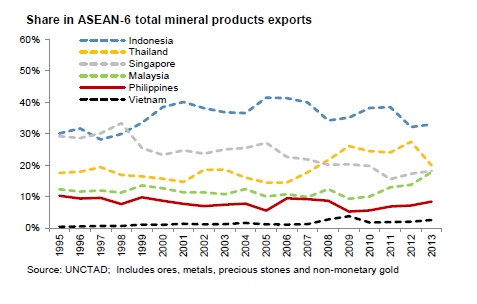

While Philippine exports have been increasing in line with those of ASEAN in response to rising external demand, the country’s share in total ASEAN-6 exports dipped to 5% in 2005 before returning to its long-term share closer to 10% prior to the trade slowdown in 2009. The Philippines exports considerably more than Vietnam, but less than the other four countries (see Figures 128 and 129).

The current mining policy framework of the country, based on the 1987 Constitution and the1995 Mining Act, is spelled out in three other documents.

• The government adopted a detailed National Minerals Policy (NMP) in December 2003, shifting “from tolerance to promotion of the mining industry.”

• In January 2004 EO 270 put in place the National Policy Agenda on Revitalizing Mining for sustainable development. The new policy “aims to promote responsible mineral resource exploration, development, and utilization to enhance economic growth in a manner that adheres to the principles of sustainable development and with due regard for justice and equity, sensitivity to the culture of the Filipino peoples and respect for Philippine sovereignty.”154

• The Minerals Action Plan (MAP), which identified special issues and concerns, was finalized and issued in September 2004 and is gradually being implemented.

• The creation of Minerals Development Council (MDC) contributed to a greater coordination among various government agencies and the private sector.

The government has identified over sixty priority mineral projects with major mineral deposits throughout the country. The projects are divided (2008 data) into (a) operating/expansion stage (12), (b) first tier priority projects construction/development stage (8), (c) feasibility/financing stage (9), (d) advanced exploration stage (11), (e) second tier priority projects (3), and (f) priority exploration projects (22).

Investment under the MAP in mining priority projects has reached US$ 2.8 billion. The inflow in 2009 was reported to be US$ 640 million, and the MGB forecasts US$ 1.4 billion in 2010, US$ 3.4 billion in 2011, and US$ 3.9 billion in 2012. The 2004-2013 cumulative investment level target of US$ 13.5 billion after five years (2004-2009), however, has fallen short and has achieved US$ 2.8 billion in actual investments.

If these investments continue to be realized, the benefits to the economy in terms of exports, jobs, and national and local revenues will be substantial. However, full development of the mining sector continues to face very significant challenges, described below and the subject of the recommendations that follow.

While the recent softening of world prices has taken some of the glitter from the mining sector, long-term prospects for the industry remain strong. Economic growth in Asia is the fastest in the world, and the region is quickly recovering from the effects of the global financial crisis. With recovery, the Philippine mining industry should position itself to better satisfy the world’s appetitefor metallic minerals.

Legal framework and policies

Long-standing complaints about the lengthy, tedious approval process for exploration permits (EPs) continue to impede investment in the mining sector. The practice of having the MGB central office review and validate approvals done at regional offices appears to be redundant and is one of the main factors causing delay. What are being applied for are only EPs, without assurance that the project is viable. There is no reasonable justification for such a lengthy bureaucratic process.

Further, when there are conflicting claims, the process becomes lengthier. Arbitration and adjudication still depends on the legal strategies and maneuverings of the conflicting parties, and the speed with which the Mines Adjudication Board and eventually the courts decide such cases.

While the Mining Act promotes the national policy of mining in provinces with mineral deposits, several LGUs have closed their provinces to mining (see Part 4 Local Government). There is a policy inconsistency between the Mining Act and the authority of LGUs in the Local Government Code. These LGUs have advocated a moratorium on mining and closed the door to mining. The DOJ and the MDC have asserted the authority of the GRP, stressing the obligation of the LGU to support the national policy agenda. Provisions in the Mining Act and also the Local Government Code stipulate that management and administration of mining is a national activityhandled by the DENR.

A related issue is small-scale mining permits granted by LGUs without coordination with the MGB, leading to conflicts with legitimate mining claim holders and contractors.

The local government’s share in mining revenues has also been an issue and a reason some LGUs object to mining in their provinces. LGUs usually have problems collecting real property taxes and income from mining companies. This is one reason some LGUs resist mining projects.

While the Mining Act allows FTAAs, there are other laws which provide for a mining contractor’s access to auxiliary rights.155 FTAAs give rights to foreign-owned companies to develop large-scale projects, to access land, to cut trees, and to exploit water resources, yet the Philippine Constitution has a 60-40 equity limitation clause on ownership of land and naturalresources.

There is an inconsistency between the Mining Act and the Indigenous Peoples Rights Act (IPRA) on the issue of request for free and prior informed consent.

The Supreme Court has completed and issued new Rules of Procedures for Environmental Cases. The main features of the rules include the Writ of Kalikasan (“Nature”) which is effectively a cease-and-desist order against supposed violators of environmental laws and government officials who issue licenses for these projects.

The concern of the industry is that the rule might cover and disturb lawful activities. This could result in serious differences between procedural rules and legitimate acts of the Executive and Legislative branches of the government. Under these rules a mining contractor operating under a valid permit could face a court order to stop operating on the basis of a mere allegation of environmental damage.

The rules also violate the long established doctrine of primary jurisdiction that asserts that where an issue can be determined by a specialized agency – such as the MGB – the courts will not involve themselves. But the proposed rules presume equal jurisdiction between the judiciary and executive branch agencies over complicated technical problems.

There is an Alternative Mining Bill known as the Philippine Mining Resources Act of 2009 introduced in the 14th Congress. This proposal seeks to cancel all existing mining permits, licenses, and agreements and declares all ancestral lands and all mineral reserves within such areas as belonging to indigenous peoples (IPs). The bill also creates a Multisectoral Council (but does not require any scientific background on mining for membership) that will decide which lands can be used for mining. The MGB will be reduced to a subsection of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

Whenever there is a change of president and DENR secretary, there is a possibility of policy change. The current policy of supporting growth of the mining sector should be continued in future administrations, as should the Minerals Development Council.Indigenous Peoples At the heart of IPRA are the rights of the indigenous cultural communities (ICCs) and IPs to their Ancestral Domains and lands, which include:

- The right of ownership sustained by the view that ancestral domains and all resources therein serve as the material basis of the IPs’ cultural integrity. These lands and resources are the IPs’ private property that they consider to be community property that has belonged to all their generations.

- The right to develop and manage lands and natural resources of their Ancestral Domain Sustainable Protection Plan (ADSPP), which they formulate themselves. This right however does not preclude other persons from undertaking business or other activities in ancestral domains, especially those involving the exploration and extraction of natural resources.

- The condition precedent of Free and Prior Informed Consent (FPIC) of the ICC or IP owning the domain should be secured and be certified to by the National Commission on Indigenous Peoples (NCIP) with a Certification of Compliance. The FPIC is very important. Gaining the FPIC from the concerned community is often seen by exploration companies as the most difficult part of the final process of acquiring a valid EP, or one of the other forms of mining agreements.

The NCIP has no budget. It is currently under the DENR. Almost all the ancestral lands exist only on paper. The NCIP lacks the capacity to map all ancestral lands and make this data available online. A mining investor cannot tell easily if the land he is considering is ancestral land. The NCIP also lacks a legal framework for an appeals process.

Another issue that needs to be addressed by mining companies is the proposed resettlement of IPs from their ancestral lands, with which they have a long-held spiritual bond, to areas outside the mining operation area.

Security Actions of the New People’s Army (NPA) can hinder access to mining sites and can be a real security problem if a company is not attentive.

Land issues Another inhibitor to growth of the mining industry is the access to land/ground. It would be helpful and conducive to industry growth for companies to be allowed free access to conduct initial geological studies, mapping, soil sampling, and limited testing either via channel sampling or use of non-intrusive man-portable drilling rigs during the pre-permitting process. The ability to carry out this work gives the company confidence in raising new capital and assists in training people within the community to undertake such skill functions as survey line markers, soil samplers, road maintenance workers, and environmental field assistants. Work accomplished would be reported in a timely fashion and would assist company applications through the bureaucratic process to the award stage.

Human resources Because the MGB is tasked to manage the mineral resources of the country, their personnel must have the skills to implement and understand the technical details of the mining industry. Too many good geologists are leaving the MGB to seek higher salaries and more attractive working conditions than are offered by government service. This results in an understaffed MGB and a growing lack of confidence by the senior staff towards building their careers and their future. Many applications are filed by parties who are not genuine exploration companies hoping that by applying for an EP it will be valuable to someone else after it has been granted. Consequently, the MGB is inundated with applications from parties who lack funding and their own technical staff who are competent to prepare mining documents.

Financing A challenge for financing mining development in the Philippines is the negative perception of the industry among financial institutions. Banks often view corruption, policy inconsistency, and church intervention in secular issues as serious impediments to mining development.

Another challenge is the creditworthiness of Philippine mining companies and mining projects. Many local companies hold mineral rights to good mineral prospects, but their balance sheets do not support their financial capability to develop their projects. Some local approved claimants have no prior experience in mining. With no mining background and lacking the data package from initial project investment (drilling, feasibility studies, resource definition) that are needed for banksto review against their project loan checklist, these claimants are rarely eligible for bank financing. A third challenge arises from the scale of junior mining players moving from exploration to extraction projects. While there may be good mineral prospects, these are usually small scaleprojects compared to large scale projects, which mining companies in Indonesia are developing,and are thus less interesting to large banks.

PerceptionsThe prevalent external perceptions are of corruption, Church intervention on mining issues, and inconsistent policy. These perceptions deter new investors.

Footnotes

- The optimistic welcome extended to the legislation was short lived, as the constitutional issue against the Mining Act and the Financial and/or Technical Assistance Agreement (FTAA) was raised by concerned indigenous people to the Supreme Court. Protracted litigation caused mining companies attracted to come in 1995 to move away due to the uncertain business climate. The industry stagnated from 1995-2004 due to this constitutional issue.[Top]

- Revenues fell in 2008 as mining industry activity slowed during the financial crisis. Source: MGB[Top]

- NSCB and NSO[Top]

- Business World, January 22, 2004[Top]

- Among the auxiliary rights granted to a holder of an FTAA are (i) timber rights or the right to cut trees or timber within one’s mining areas that are necessary for the mining operations; and (ii) water rights or the privilege granted to appropriate and use water. In the case of timber rights, a private land timber permit can only be issued under the relevant forestry laws to owners of private lands covered by titles or other recognized certificates, who are necessarily Filipino citizens or corporations. Thus, in the case of a foreigner holding an FTAA, it is still unable to qualify for such timber rights. Similarly, for water rights, only Filipino citizens or corporations may be granted such under the Water Code of the Philippines, and consequently, a foreign FTAA contractor will not qualify to be granted such rights. These examples show a seeming disconnect between an innovative legislation such as the Mining Act that allows foreigners greater rights and earlier nationalistic provisions found both in the Philippine Constitution and the forestry laws and water code that limit the enjoyment of certain rights relating to the country’s natural resources to the State and to its citizens. Moves may thus be directed at studying how to reconcile liberal statutes with those that impose nationality restrictions.[Top]