Judicial

Filipinos and foreigners alike have long urged reforms in the administration of justice in the Philippines. Among the most common observations are clogged dockets resulting in long periods before decisions are promulgated, Supreme Court rulings that negatively affect the business and investment climate, the use of courts and sheriffs for legal harassment, including the questionable issuances of Temporary Restraining Orders (TROs).

The Supreme Court is responsible for administering the judicial system and has for some years been implementing foreign donor assisted projects that have assisted the court’s reform priorities in several areas. Judicial salaries were increased under RA 9227, which helped reduce the 30% vacancy rate for judges. Increasingly, judges are being disciplined for infractions. The incidence of issuances of arbitrary TROs against foreign companies has fallen. The total caseload of all courts peaked in 2000 and has since gradually declined. The Alternative Dispute Resolution Act of 2004 has encouraged more parties to arbitrate their cases rather than using the courts.

“The Supreme Court… all filled… must be decided or resolved within twenty-four months from date of submission, twelve months for all collegiate courts, and three months for all other courts”

—Article VIII, The Philippine Constitution

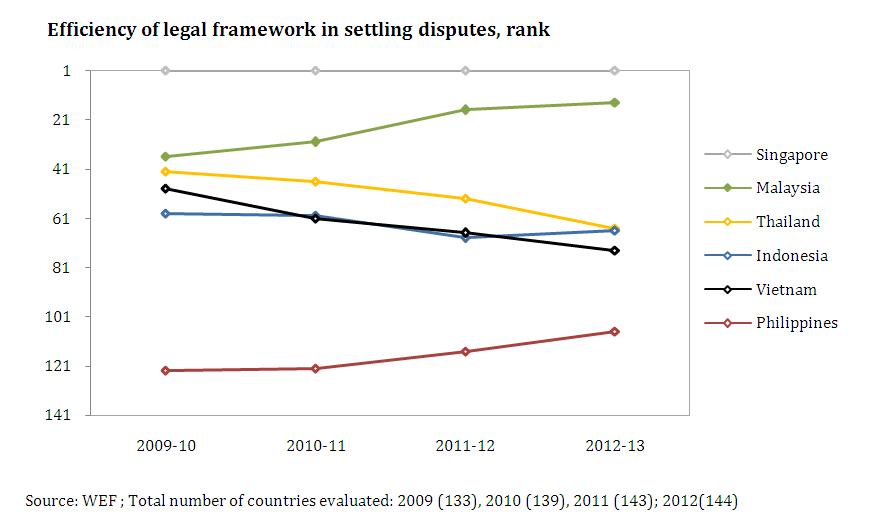

Despite this laudable progress, the Philippines remains very poorly-rated in the Global Competitiveness Report 2010 for its efficiency of legal settlement, ranking very far below the other ASEAN-6 and 123 of 133 countries globally (see Figure 174).

View original figure here

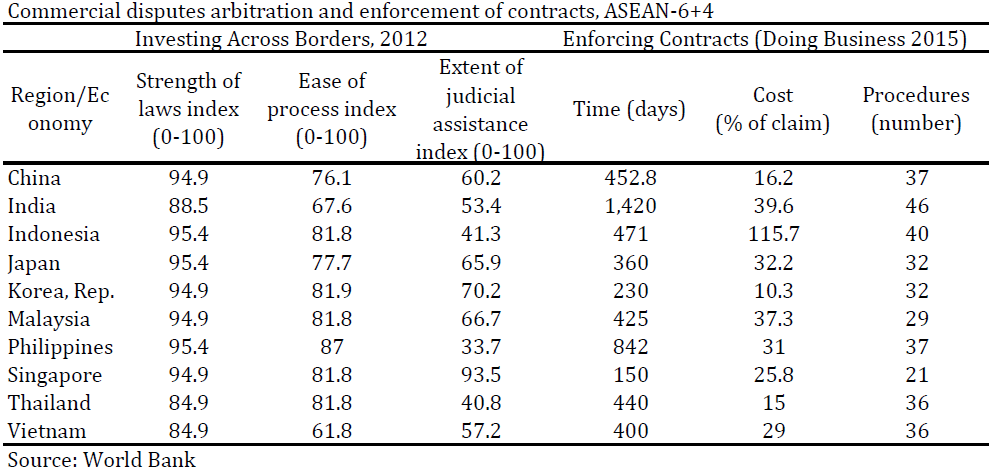

Another comparative measure, in two World Bank reports, shows the Philippines requiring 37 procedures taking 842 days (more than two years) for enforcement of contract, which required 21 procedures and 150 days in Singapore. However, the Philippines was the highest-rated among the ASEAN-6 + 4 Asian group for the strength of its laws for arbitration of commercial disputes and the ease of the arbitration process. Unfortunately, the commercial arbitration process was extremely low-rated for the extent of judicial assistance, suggesting that courts prefer to decide themselves cases brought to them. These ratings argue that more disputes should be arbitrated and that the courts should encourage the arbitration process (see Table 68).

View original table here

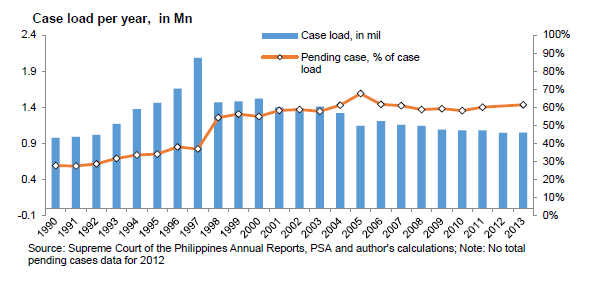

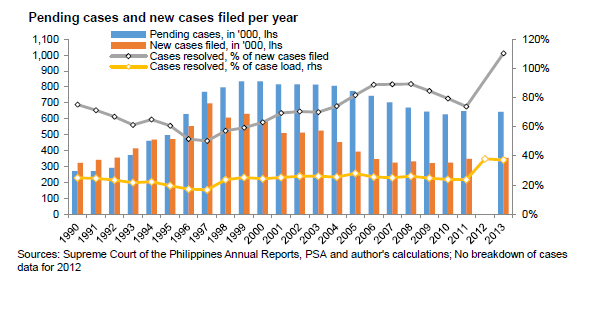

The total caseload of Philippine courts more than doubled to 1.5 million in the decade ending in 2000. Since then, the caseload has declined significantly to around one million (see Figure 175).

Figure 176 shows a decline in the case backlog beginning in 2000, a decline in the volume of new cases filed, and a fifty percent increase in the percentage of new cases resolved.

View original figure here

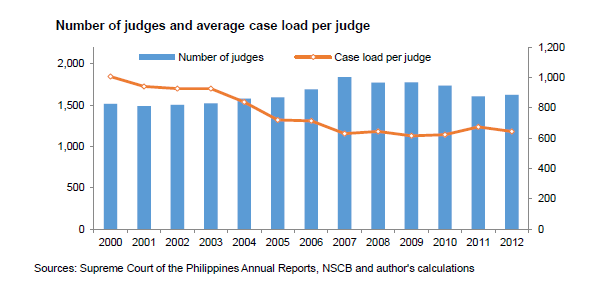

Figure 177 shows that the number of cases per judge has declined by about 50% as the number of judges has increased. With more judges handling fewer cases each, then the case backlog should shrink and the delivery speed for judicial decisions should improve. In a mid-2010 speech, Chief Justice Corona reported that there are 1,771 judges serving out of a total of 2.29 positions with total vacancies numbering 519 or 22.7%.

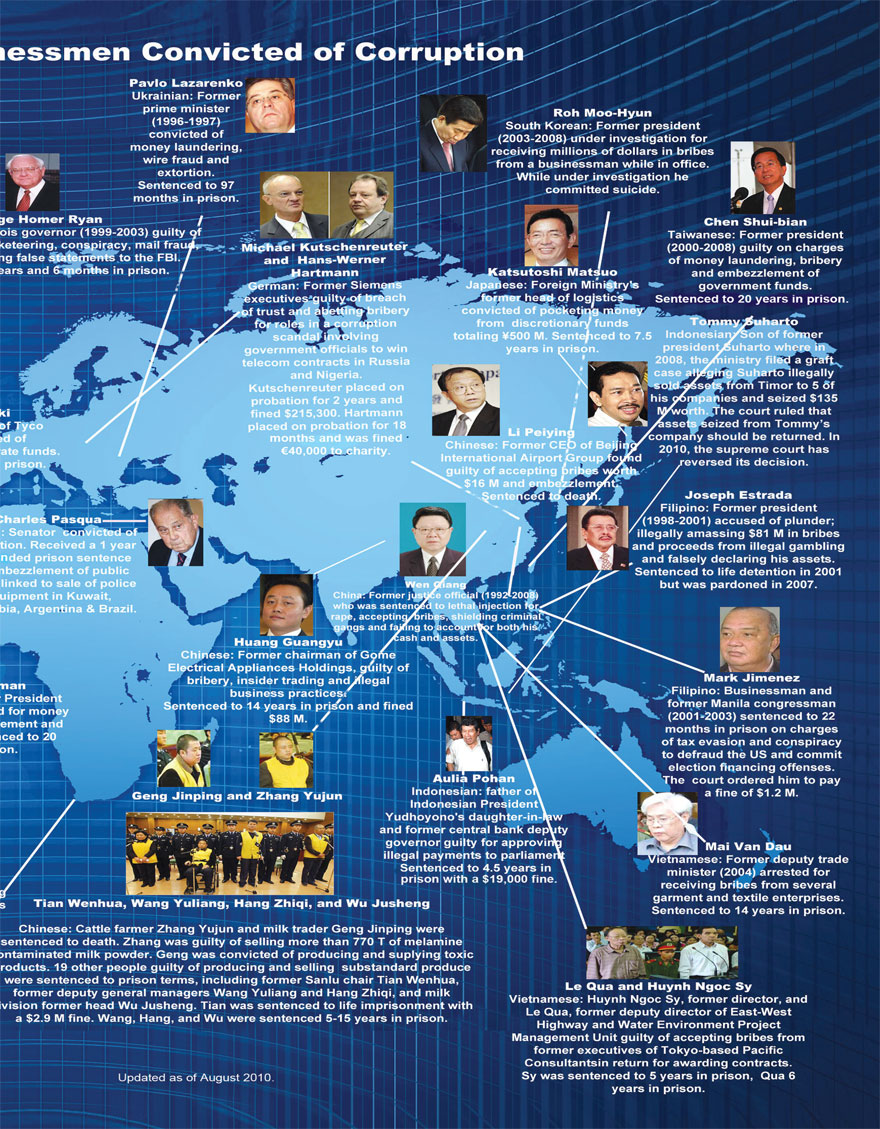

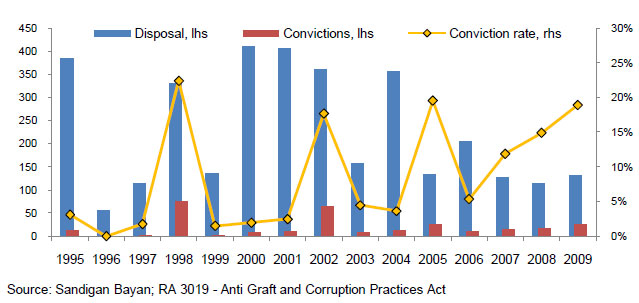

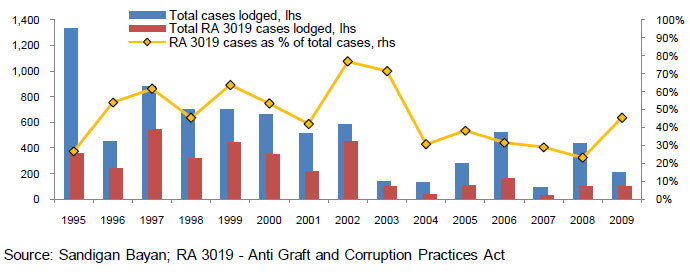

Data on court convictions proved difficult to research. However, the Sandiganbayan provided statistics for a period of 15 years for cases involving RA 3019, the Anti-Graft and Corruption Act (see Figures 178 and 179). The Sandiganbayan is the special court for trying government officials, whose most famous case was the trial and conviction of former president Estrada in 2007. The total number of cases filed before the Sandiganbayan for graft and corruption violations has fallen consistently since 2002 and has remained lower than under previous presidents Ramos and Estrada. However, in recent years, the percentage of total cases disposed of resulting in convictions increased to 20%.

total number of complaints per year, 1995-2009

“A corrupt judiciary is totally unacceptable as it severely handicaps the legal and institutional mechanism designed to curb abuses in government ”

—Chief Justice Renato Corona, quoted in Manila Bulletin, June 28, 2010

Supreme Court Decisions.

As the ultimate interpreter of Philippine law, the Supreme Court has a critical role to play in decisions that can impact on the country’s business and investment climate. In the course of their legal careers, justices have little opportunity to become very familiar with the economy and business affairs. Some observers have criticized the court for decisions with harmful consequences for the business environment.

However, the court appears to have become more cautious about potentially harmful consequences to the nation’s business and investment climate of major legal decisions. Its rulings that are supportive of the economy should also be better researched and recognized. Too often decisions with negative consequences are remembered better than those with positive ones. Examples of the latter include the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Clean Air Act that incineration can take place so long as harmful gases are not released (2002); its reversal of its position on the Mining Act (2004); and its order to several government agencies to clean up and rehabilitate the polluted Manila Bay (2008).

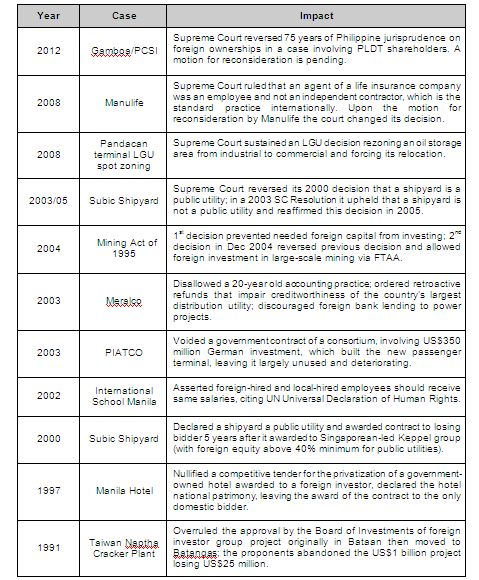

Nonetheless, there were cases in which the Supreme Court appeared to favor domestic interests over foreign investors, and the Supreme Court has issued a number of controversial decisions having negative effect on the business and investment climate of the country (see Table 69).

As a possible ameliorative measure, the Supreme Court could more frequently request amicus curiae expert advice in cases impacting on the business environment. In making various decisions where the court believes it lacks expertise, the Supreme Court has sometimes requested experts to provide testimony. This same procedure should be followed when important economic issues are decided.

In August the Supreme Court ordered a TRO on the national government applying the VAT to toll road fees, with the opponent arguing that only the Congress can initiate this taxation. A Malaysian company which had completed an extension of a heavily-used toll road that connects it to another toll road and saves time for travelers refused to open the new road until it knows what its revenue stream will be like. Such judicial intervention come at a time when the new Aquino administration intends to promote investment by the private sector in infrastructure projects and the decision of the Supreme Court will be carefully watched by domestic and foreign investors.

The docket of the Supreme Court is one of the most crowded in the country. According to a former Chief Justice, the court has some 7,000 cases divided among its 15 members.<sup “>221 New cases arrive every month. The Supreme Court now uses computers to track the status of cases with the goal of delivering justice faster.

The heavy load of cases of the Philippine Supreme Court could be reduced through greater selectivity. Compared to many countries, the court assumes a tremendous burden of cases, so that it is challenged to meet the constitutional requirement to reach decisions within 24 months. By contrast, each year, the US

“The Supreme Court has struggled to speed up the delivery of justice by… ordering continuing trials for certain cases, filling up(judicial vacancies), encouraging the use of arbitration and mediation, increasing the compensation of judges, computerizing court processes… etc.”

—Speeding up Quality Justice, Artemio V. Panganiban, PDI, September 10, 2010

Headline Recommendations

- Continue judicial reforms to speed up justice in all courts by hiring more judges and increasing salaries. Continue to reduce the caseload of all courts by more encouragement of arbitrated settlements in civil cases. Improve BIR, BOC, and Ombudsman legal staff to prepare better cases with better prospects of successful prosecution and conviction.

- The Supreme Court should request amicus curiae expert advice in ruling on issues that may adversely impact on the investment climate. The Supreme Court could reduce its caseload by being more selective in accepting case. Rules of the Court should be changed to recognize foreign arbitration decisions without reopening cases.

- Create a special court for Strategic Investment Issues. Oversee the environmental courts so that application of Philippine environmental laws strongly supports responsible mining practices.

Recommendations: (12)

A. Continue to increase judicial salaries and hire more judges, encouraging new judges to reduce the case backlog even more. Steadily raise the budget for the judicial branch from the present 0.008% of the national budget. (Medium-term action Supreme Court, DBM, and Congress)

B. Discipline errant judges who do not follow the rules of the court or the laws of the land. (Medium-term action Supreme Court)

C. Avoid capricious and arbitrary TROs, which too often are unfair to one party in a dispute. (Medium-term action all courts)

D. The Supreme Court should request amicus curiae expert advice in cases impacting on the business environment. (Immediate action Supreme Court)

E. Make greater use of alternative dispute resolution and arbitration to resolve civil disputes outside of courts, which should reduce the backlog of cases and hasten justice. (Immediate action all courts and the private sector)

F. In order to strengthen foreign arbitration it will be essential to change the “rules of the court.” While Philippine law provides that all arbitration awards have to be confirmed by Philippine courts for execution, it is necessary that the courts not reopen the cases but just confirm them. Reopening of cases should be limited to proven gross negligence of the arbiters. (Medium-term action Supreme Court)

G. Reduce the caseload of the Supreme Court by limiting acceptance of cases largely to cases involving national issues. (Medium term action Supreme Court)

H. Create a special court for Strategic Investment Issues where the justices have been chosen based on familiarity with international investment and business issues and laws. (Immediate action Supreme Court)

I. Oversee the environmental courts in administering the Writ of Kalikasan so that application of Philippine environmental laws supports responsible mining practices and results in substantial socio-economic benefits for the Philippines. (Medium term action Supreme Court)

J. The Ombudsman should increase its investigations of allegations of corruption against public officials. The Sandiganbayan conviction rate should continue its increasing rate of convictions for graft and convictions. (Immediate action Ombudsman and Sandiganbayan)

K. The legal divisions of the BOC and BIR should be given the resources and management leadership to prepare smuggling and tax cases more thoroughly to increase the chances for successful prosecution and conviction. (Medium-term action BIR, BOC, DOF, DOJ, and courts)

L. End harassment seizures of private businesses by sheriffs. (Immediate action all regular courts)

Footnotes

- When he arrived at the Supreme Court in 1995, he found a case among the 1,200 assigned to him that had reached the Supreme Court ten years before, involving a man convicted of murder. Upon review the evidence against him was found weak, and he was released from Bilibid Prison after 20 years there. Former Chief Justice Artemio V. Panganiban in a column in the PDI, September 12, 2010.[Top]